In 2007, Chiou-Rong Sheue and colleagues published the discovery of a new type of chloroplast, called the bizonoplast. The bizonoplasts found deep within the cells of the spikemoss Selaginella erythropus was unique among its chloroplast kind in several ways.

To begin with, it was alone, existing in solitary confinement within the plant cell. This finding in itself is not completely surprising. Monoplastidy- the act of having a cell with just one chloroplast- is lacking in nearly all other vascular plants*. Most plants seem to prefer to have multiple chloroplasts in each cell, presumably to add a certain amount of redundancy to the system in case one of the power-giving compartments stops working. But monoplasty in Selaginella has long been recognised as one of the ‘major peculiarities’ of this genus, having been discovered as far back as 1888. So what made bizonoplasts special was not just the fact of being alone, but the fact that they were alone, the fact that they were oddly shaped, and the fact that they were huge.

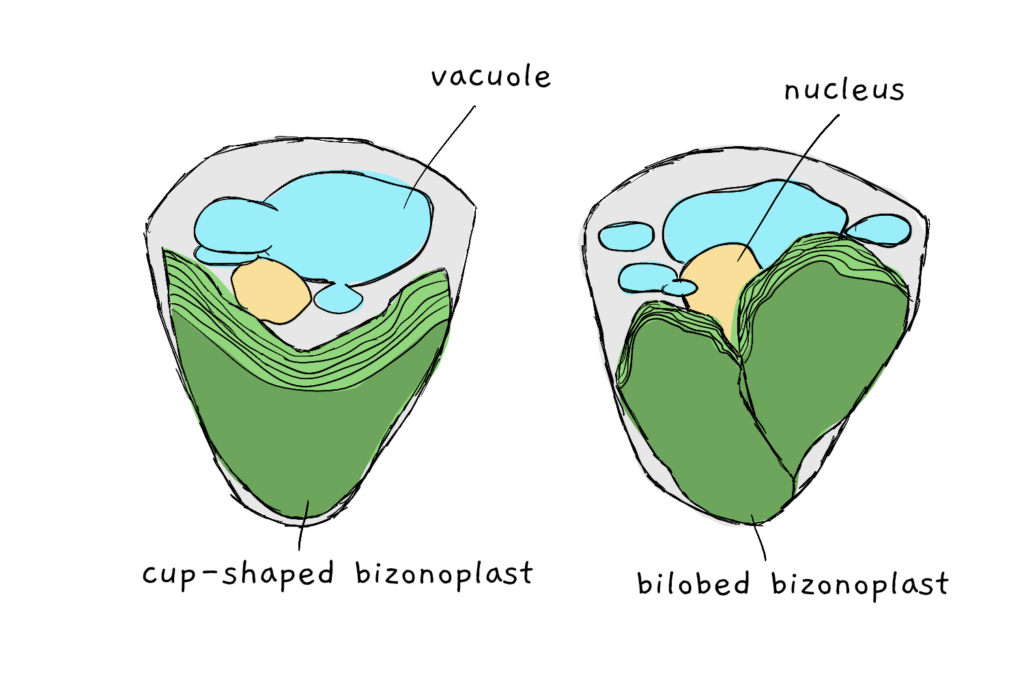

The bizonoplasts had length, width and height dimensions roughly two-three times larger than the average chloroplast: resulting in a massive volume that took up a hefty portion of the plant cell. Their shape was odd too. While chloroplasts tend to be thought of as roughly oval or bean-shaped, the giant bizonoplasts looked like drinking cups. And that cup was very much only half full: while the bottom portion of the bizonoplast contained the expected thylakoid membrane structures that house the proteins required for the light reactions of photosynthesis, the upper zone was largely empty.

So why such such an oddity, and why in Sellaginella?

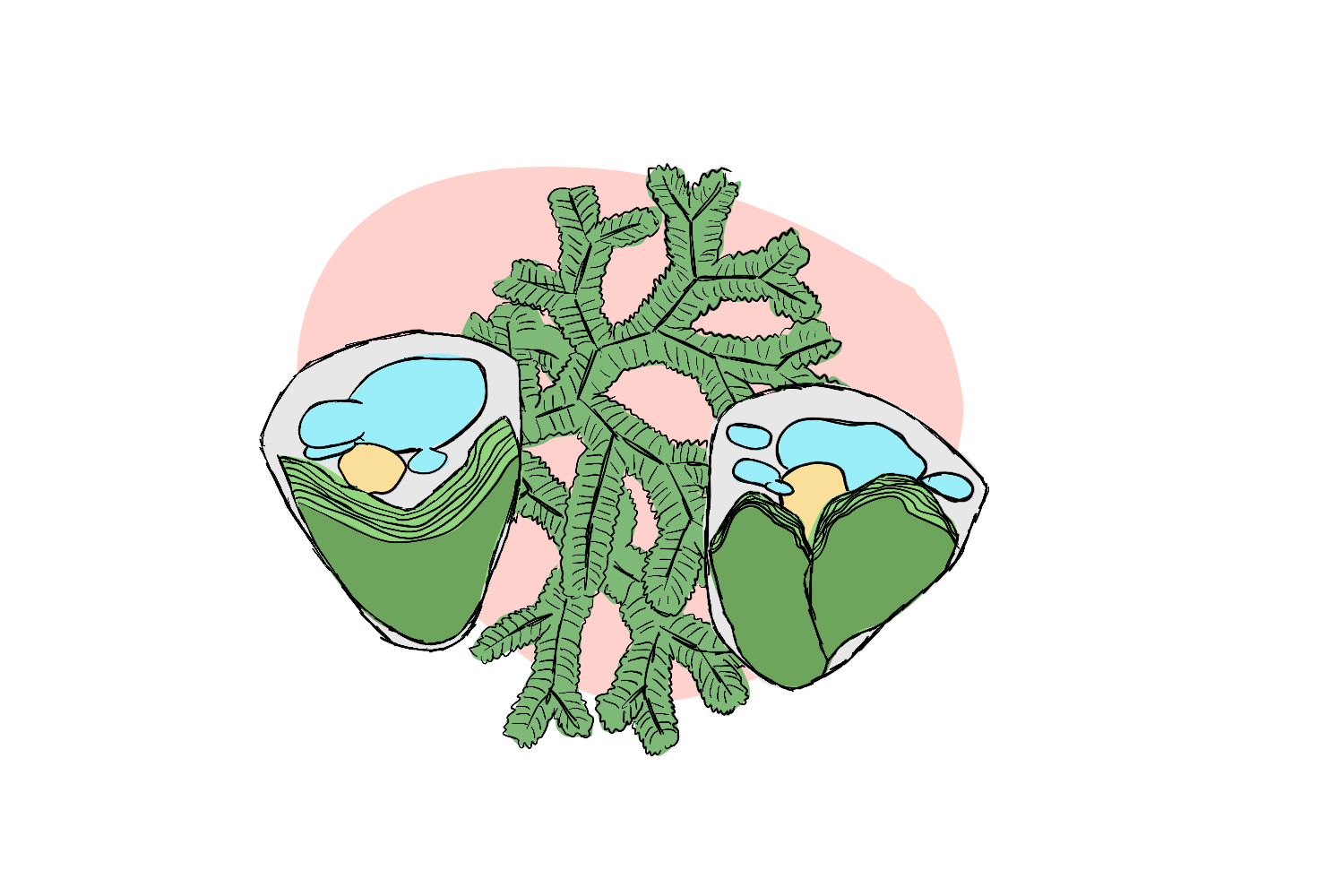

Determined to better understand the purpose and prevalence of these bizarre bizonoplasts, Jian-Wei Liu and colleagues, led by Chiou-Rong Sheue, sliced into 76 different species belonging to the Selaginella genus, and took a look at their chloroplasts.

The scientists found an amazing diversity of chloroplast type, even within a single plant – ranging from giant cup shaped chloroplasts, disc like chloroplasts, elongated or bead like chloroplasts, as well as specialised chloroplasts for both the trichomes (leaf hairs) and the cells adjacent to the stomata (air holes).

Amongst the 76 examined Selaginella species, 49 had monoplastidic cells somewhere in the plant. And of these monoplastidic cell-containing plant species, 11 of the species were also found to contain the bizarre bizonoplasts. What was also apparent, was that while species that had multiple chloropast-containing cells lived largely in open places- receiving, on average- 40% of full sunlight- the monoplastidic plants liked it dark. Bizonoplasts were only found in deep shade species, those receiving less than 2.1% of full sunlight in their natural habitat.

In addition to this shade association, the scientists discovered that bizonoplasts could be found in two forms- the cup-shaped form described earlier, and a second, bi-lobed type.

Their observations suggest that the angle between the two lobes could change in response to light. Similarly, the concave top of the cup-shaped bizonoplasts was found to have some light-dependent flexibility. These findings, together with the discovery of the bizonoplasts’ low-light correlation, raises the intriguing possibility that that bizonoplasts have evolved to help certain Sellaginella species survive in very low light, and that they are structurally designed to be adaptable to changes in light intensity within these environments.

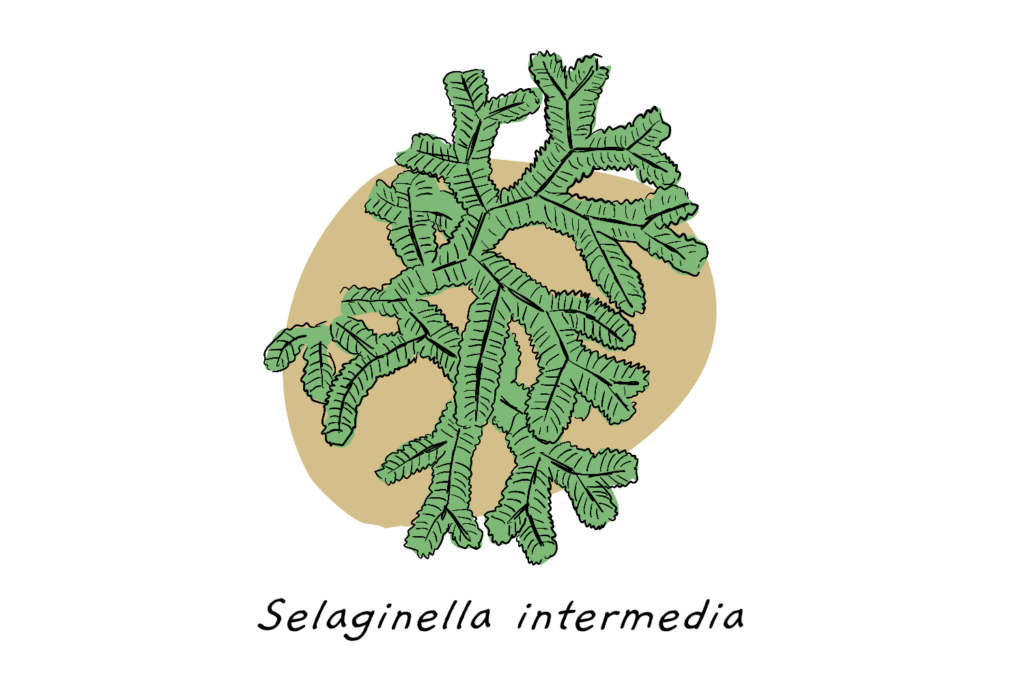

Selaginella are widely distributed across the world- with the Selaginellaceae family adapted to environments ranging from sparse desserts to tropical and leafy forests. In this study alone, the studied species lived in environments receiving as little as 0.4% full sunlight, to those receiving about 50% full sunlight: a difference of more than 100 fold. The great variety of chloroplasts found within these plants, and the specialised nature of their bizarre bizonoplasts, may hold the secrets to their success across this wide range of habitats.

* the non-vascular hornworts also can exhibit monoplastidy. To read more about hornworts, go here.

References:

Bizonoplast, a unique chloroplast in the epidermal cells of microphylls in the shade plant Selaginella erythropus (Selaginellaceae) Chiou‐Rong Sheue Vassilios Sarafis Ruth Kiew Ho‐Yih Liu Alexandre Salino Ling‐Long Kuo‐Huang Yuen‐Po Yang Chi‐Chu Tsai Chun‐Hung Lin Jean W. H. Yong Maurice S. B. Ku 2007 American Journal of Botany

Liu JW, Li SF, Wu CT, et al. Gigantic chloroplasts, including bizonoplasts, are common in shade-adapted species of the ancient vascular plant family Selaginellaceae. Am J Bot. 2020;107(4):562-576. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1455 (Full pdf on ResearchGate)