The orchid family, Orchidaceae, contains over 750 genera, yet it is the Catasetum genus that has earned a description from non other than Darwin himself as ‘the most remarkable of all Orchids’. Probably because, while other pollinated plants like to offer their pollinators a treat, Catasetum orchids also bring the trick.

Catasetum orchids like to beat up bees. I’m not trying to say that they enjoy it, in an active and emotional way. But they do seem to benefit from it.

Let me explain.

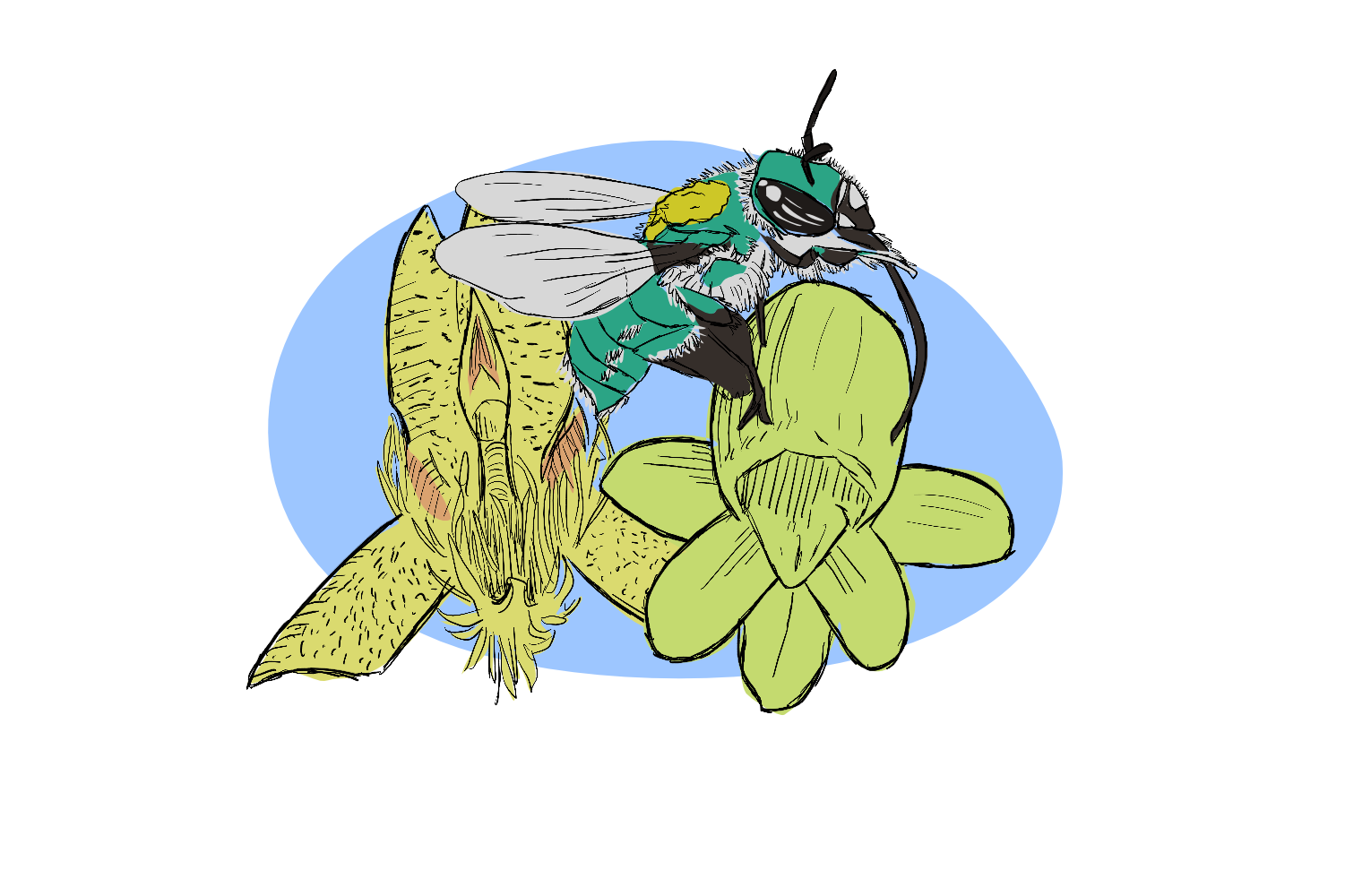

Male flowers – Catasetum orchids have flowers of separate sexes – utlize a remarkable ejection mechanism for their pollen. The colourful and aesthetically pleasing flowers include a pair of antennae-like structures, which act as a tripline for the bees that dare to visit. Within milliseconds of disrupting the antennae, a pollen-projectile is shot at the insect, and firmly adhered to its back, perfectly possitioned for pollination of female flowers that might be visited at a later date.

The pollen is not so much gently placed, as forcefully shot. I think the most analogous modern image I can provide to conjure up the voracity with which this orchid beats up on bees is the infamous Whomping Willow from Harry Potter. The bee is, very much, Whomped. And it doesn’t enjoy the feeling.

To put it into science speak: emplacement [of the pollen] was adversive.

So why would the plants hurt the very animals that help them do the reproductive deed? Way back in the mid 1980s, Romero and Nelson investigated the evolutionary implications of such abusive behaviour. They found clear evidence that, while naive un-whomped bees were happy to visit either male or female flowers, bees that had been whomped actively avoided other male flowers.

But they didn’t avoid females of the same species.

A very important part of this equation, is the fact that the Catasetum orchids not only produce flowers of different individual sexes, but also that the two flower types look very different from eachother. This feature, known as sexual dimorphism, is widely known in colourful birds and butterflies, but is not super common in the plant world. Interestingly, just like some of these dimorphic animals, when Catasetum orchids were first found in the wild, male and female flowering plants were believed to belong to different species entirely!

In any case, once bees have been whomped by Pollination Power, steered clear of other visually-male flowers, but instead flitted from female to female (female flowers and male flowers produce the same chemical attractants that lure the bees in). All in all, a perfect way for the male flower to ensure that its own genetic material was passed to as many females as possible, and had limited competition from other males

One quite ingenious element of the whole interaction, is that Catasetum species that dumped a heavier pollen load on their pollinators (up to 23% of the bee weight), seem also to have evolved to have greater differences between the flower sexes. So that the greater the trauma, the greater the effort made to convince the pollinator that the female flowers were definitely different from the males!

Finally, the scientists noticed that the sex ratio of flowers in the population was heavily skewed, so that there were multiple males for each female. This ratio might well be a strong argument for the (evolution of the) aggressive behaviour of male flowers – which must use tricky tactics to ensure their genes are passed onto the next generation

Overall, the behaviour of Catasetum orchids definitely has us agreeing with Darwin’s call of remarkability… even if we do feel a little bad for the bees.

References:

Romero GA, Nelson CE. Sexual dimorphism in catasetum orchids: forcible pollen emplacement and male flower competition. Science. 1986 Jun 20;232(4757):1538-40. doi: 10.1126/science.232.4757.1538. PMID: 17773505.

Full text available via ResearchGate.

Charles C. Nicholson, James W. Bales, Joyce E. Palmer-Fortune & Robert G.

Nicholson (2008) Darwin’s bee-trap: The kinetics of Catasetum, a new world orchid, Plant Signaling & Behavior, 3:1, 19-23, DOI: 10.4161/psb.3.1.4980

Check out a video here

Read more here