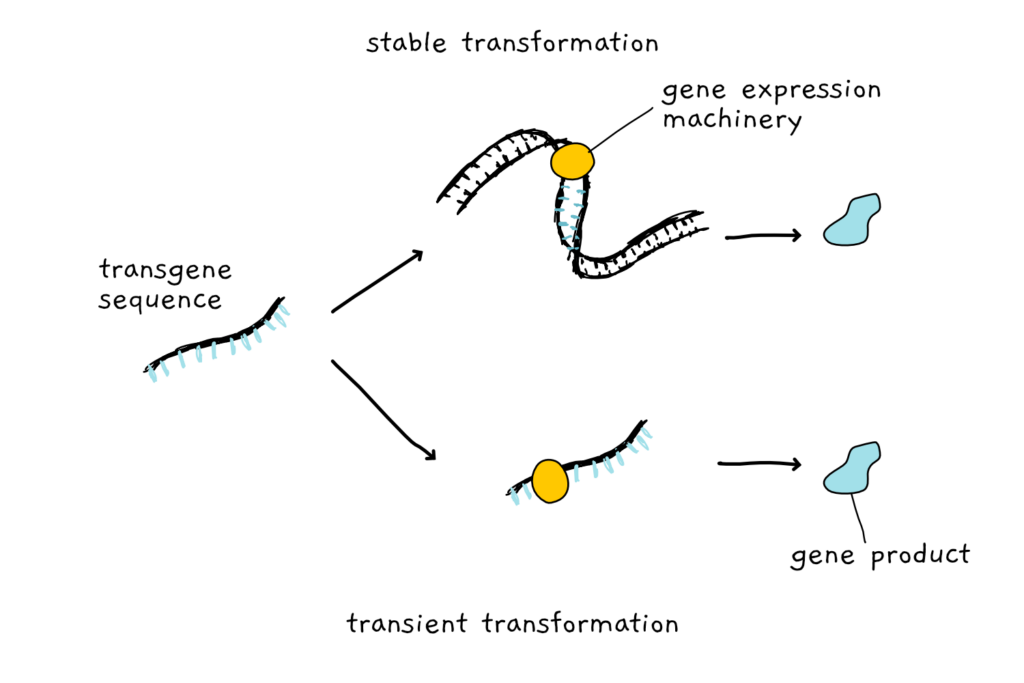

Genetic transformation – the act of adding or removing genes in an organism – can be done two ways. Stable transformation involves getting the foreign DNA to actually integrate into the genome of the transformed species, so that the newly integrated DNA can be passed on from generation to generation.

Alternatively, instead of integrating the piece of foreign DNA permanently in the genome, it is just brought to the cellular gene expression machinery. The cell’s enzymes start reading the DNA and turning its genes into products only for as long as the DNA hangs around- the transformation is transient. If the cell divides it often means the end of the transient gene expression.

While many plants are not accessible by molecular tools for stable integration of a foreign DNA, they might be accessible for transient transformation. Getting a piece of DNA to hang around for long enough to be actively expressed is a step easier than having to integrate that DNA into the genome.

A hot target

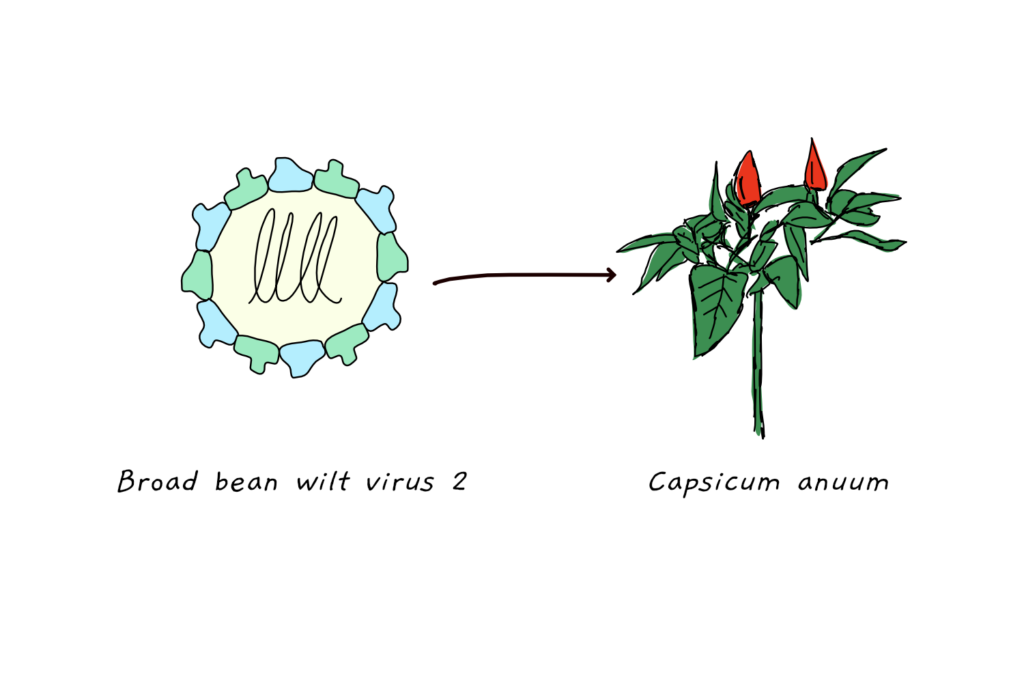

Pepper, or Capsicum anuum, is an important crop plant that cannot yet be stably transformed. One of the first steps of modern breeding is understanding the function of different genes, to then select targets for selection. Basic research usually provides this information through the molecular study of mutants, overexpressors or transgenic plants. In pepper, this has barely been possible. While isolated cells could be transformed transiently, no functional gene studies could be performed in planta.

Boram Choi, and his colleagues from Seoul National University, set out to change that. They designed and created a virus based system that can transiently express genes throughout the entire pepper plant. Additionally, they adapted their system to follow a previous method- known as virus induced gene silencing (VIGS)- which allows transient disruption of genes. The tool set offers new and effective ways to study gene functions in pepper, and potentially opens up the field for other species too!

The beauty of a virus system is that it self-amplifies. A small infection can quickly overtake the entire plant – a useful feature if you want to introduce a foreign sequence. The downside of viral systems is their virulence (harmfulness). In nature, viruses infect plants and lead to growth defects or the death of affected plant organs. Unsurprisingly, a system that delivers a gene sequence and at the same kills the plant is very limited use.

Taming a virus

The researchers circumvented the problem of virulence by carefully selecting the virus they used to carry the gene sequence. Broad bean wilt virus2 (BBWV2) usually infects beans but has a wide host range. In pepper, it is able to infect the entire plant without causing any observable change to the system.

The research team then engineered BBWV2 to carry a transgenic sequence. They tested two genes of different size to test the capacity of the virus. The gene size is limited as the virus has to pack the genetic information into its shell – and larger genes take up more space. The found that only the smaller gene resulted in a spread of the virus, the leading to the conclusion that the upper limit for transgenic sequences lies around 2 kb. While 2 kb is not exactly large when it comes to gene size, it does allow the study of a number of relevant genes.

To then further improve the system, the scientists added sequences that further increased the expression of their transgenes and added the capability to not only introduce but also knock down genes. Taken together, the virus system provides a new and capable entry point into the genome of pepper.

The foundational work laid out in studies like this enables researchers and breeders alike to better understand crop plants and potentially even improve them.

References

Choi, B., Kwon, S.-J., Kim, M.-H., Choe, S., Kwak, H.-R., Kim, M.-K., … Seo, J.-K. (2019). A Plant Virus-Based Vector System for Gene Function Studies in Pepper. Plant Physiology, 181(3), 867–880.