The other day, my friend and I were musing over the fact that many flowering plants require a third party pollinator in order to complete the fairly simple act of reproducing. And that while this sexual ‘three-or-moresome’ has some pretty great advantages, it also forces plants to spend a fair amount of energy just in attracting the middle men.

Many flowering plants can self pollinate- a process in which the pollen from one flower fertilises that flower’s own egg. But self pollination has a couple of disadvantages. Most obviously, you’re mating with yourself, which really limits the genetic diversity potential of your offspring. And in an ever-changing world, diversity is key. Secondly, you limit the chance of spreading your genetic material physically throughout the lands (although admittedly, many plants get around that barrier by making either tasty fruit or floaty seeds that spread their offpsring post-fertilisation).

So in order to send their pollen off into the world and increase the genetic diversity of their children, many plants petition pollinators to get involved in their sex lives. Of course, this relationship requires some sort of trade, so flowers offer nectar and other rewards, while advertising their goods with floral size, shape, colour and scent.

Although certain plant species have become experts at attracting just a single type of obscure wasp, it’s generally believed that attracting a wide range of pollinators has an advantage over attracting just one. Therefore, within a plant species, it can be advantageous to have a range of flower types to get maximum attraction.

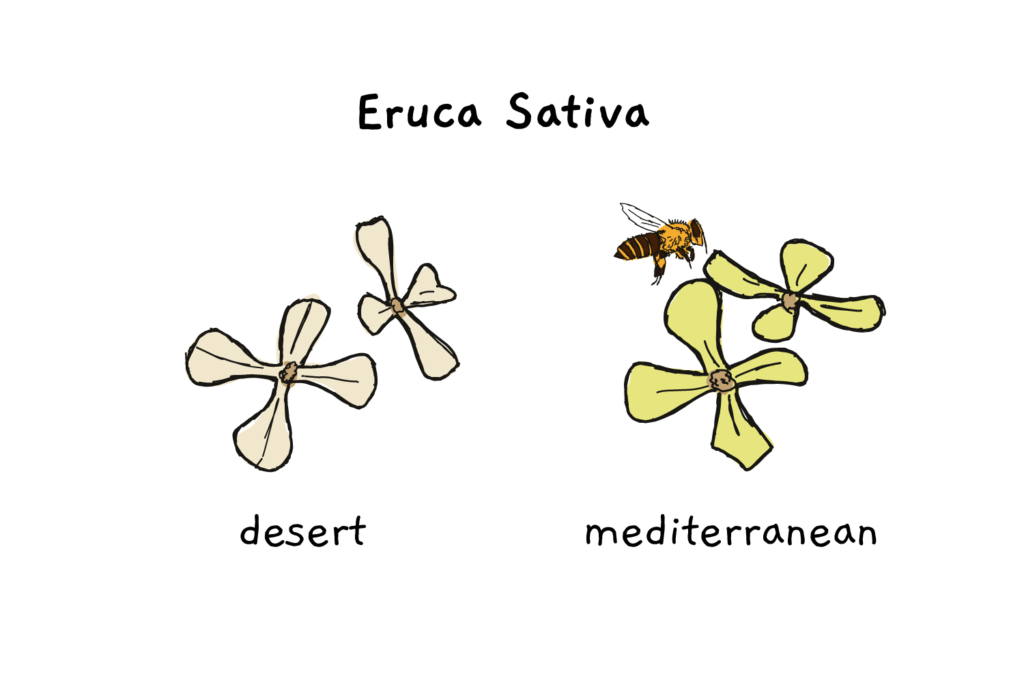

Eruca sativa is a Brassicaceae (i.e., related to Arabidopsis, and other cabbage-y friends) that grows in both desert and mediterran climates in Israel. Although Eruca generally makes pale flowers, scientists noticed that the flowers of the mediterranen populations were generally more vibrant yellow in colour, with shorter petals, while the desert individuals were more likely to have long petalled cream flowers.

In order to investigate the factors that contributed to this population-dependent colour bias, the scientists turned to the bees…

Eruca sativa is a self-incompatible species, meaning that it requires a pollinator in order to make it to the next generation. So it seemed pretty likely that pollinator preference might drive some pretty strong selection for flower colour. In order to test this theory, Barazani and colleagues took flowers from the desert and mediteranean populations, and offered them to some honey bees (Apis mellifera), to see if the bees showed a preference.

Which they did.

Honey bees commonly chose the more yellow flowers over the cream flowers, and were more decisive in their choices when yellow flowers were present (they didn’t buzz around a whole lot of the flowers but instead made a literal beeline for the yellow ones). Over the life of the plant, the yellow colouring of flowers also positively correlated with the number of fruit produced, and the mass of seeds, suggesting that being more yellow makes you actually fitter in the wild.

So it seems fairly feasible that honey bee pollinators drive the Eruca population to become more yellow with time. But while this explains the dominance of yellow flowers in the mediterranean environment, it doesn’t explain why desert flowers are more commonly cream.

One possibility, is that the desert flowers have evolved to attract a slightly different set of pollinators. Another possibility is that the desert plants have their flower colour selected by non-pollinator pressures, such as herbivore foraging. Or, that the flower colour is indirectly selected due to its correlation with other traits required for desert survival.

Supporting this second theory, is the tale of Lysimachia arvensis. Commonly named the ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’, this species in fact exists in populations of both scarlet and blue pimpernels. The blue flower type is found more commonly in the south, while the red is found in the north. Although technically the same species, the two types show marked differences in flowering time, which generally prevents them from cross breeding even in places where they grow together.

As it turns out, both the red and blue types are capable of self-pollinating, and no studies have shown that pollinators prefer one colour over the other. This suggests that a factor other than bees and their friends might be driving pimpernel populations. Various experiments revealed that, while the blue flowering plants were generally fitter, the red flowering plants reigned supreme in sun-wet conditions. Although once again, it’s not clear what exactly is contributing to this fitness, but there does seem to be linkage to the colour of the flowers.

So, while plants hand over a whole lot of power to pollinators, it turns out that those pollinators are not the bee* all and end all.

*I’m not even sorry.

References

Natural Variation in Flower Color and Scent in Populations of Eruca sativa (Brassicaceae) Affects Pollination Behavior of Honey Bees. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6516435/

Abiotic factors may explain the geographical distribution of flower colour morphs and the maintenance of colour polymorphism in the scarlet pimpernel https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2745.1211